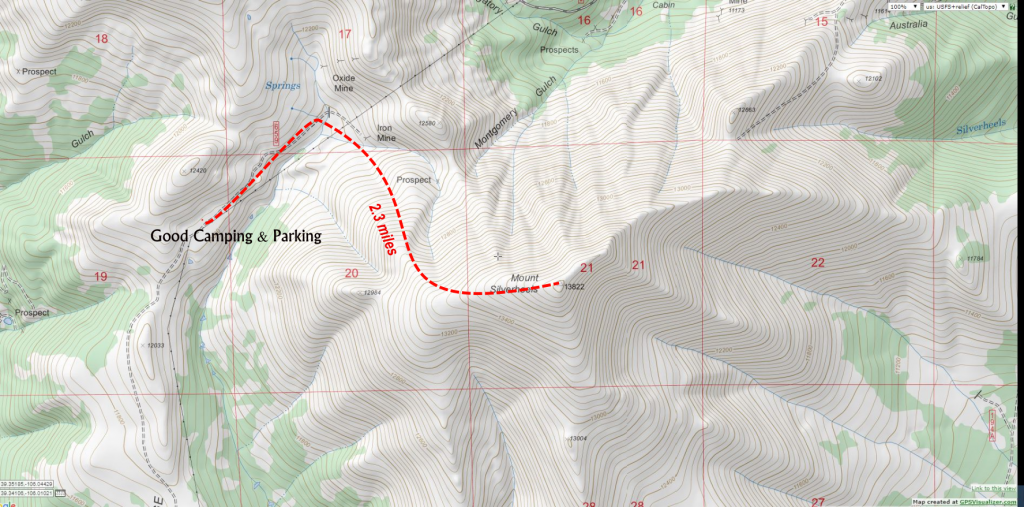

Downloads: GPX File | KMZ File for Google Earth

Mystic looks east from the summit of 13,822′ Mount Silverheels.

Mount Silverheels checks in as Colorado’s 96th tallest ranked summit. At 13,822’, it’s technically a Front Range mountain, but as a hike, it’s more like a classic Sawatch Range Peak: long, gentle, slopes that top out on a rounded summit with spectacular views. Silverheels is somewhat tucked away, despite its hulking presence from popular vantages points such as Boreas Pass. As a result, there are no established hiking trails to the top.

What it lacks in popularity it makes up for in legend. The memorable moniker is named after a popular dance hall girl who wore the apocryphal silver heels—geographic features named after women of both favorable and ill repute is common in Colorado. As the legend goes, this mysterious woman had a heart as big as her… heels. While others fled the area during outbreaks of sickness, she stayed to comfort the remaining miners. Silverheels herself was said to have come down with a case of smallpox that permanently scarred her face, so she resorted to wearing a blue and white mask that further obscured her true identity. Eventually, both Silverheels and the town she inhabited, Buckskin Joe, disappeared into Colorado lore. Whether or not Silverheels actually existed remains up to debate, but the mountain named in her honor is very real.

Most people access Silverheels from Hoosier Pass, mostly because of the ease of parking. We opted to hike the mountain from the less popular West Side via Forest Service Road 659. My main motivation in choosing the less-traveled route was to explore the low-traffic basin and mining ruins in the area. A surprisingly well-maintained 4×4 road climbs just over 12,000’. A series of space-age looking power towers stand in line in the open mountain tundra. These massive metallic sentries add a surreal element to the otherwise pristine backcountry. In fitting fashion, the towers’ silver-white skin gleams under Rocky Mountain sunshine. My guess is that whatever enterprise maintains these towers is responsible for the upkeep of the road. (For directions and driving info, read the directions at the end of this post).

Forest Road 659 was better maintained than the access road to reach it, Beaver Creek Road. Beaver Creek Road wasn’t anything crazy, but it is riddled with tooth-jarring washboard ruts. After passing a cattle gate (which serves as a winter closure), the road ascended from about 10,000’ through dense willow thickets before climbing up a scrappy-but-not-technical hill to 11,800’. I almost had to put my 4Runner into 4-Low here. This hill is the most challenging part of the drive up. Stock SUVs and even vehicles like Rav4s and CRVs can make it up this road—I’d even say that a very carefully driven car could make it up, though I’ve knocked enough exhaust parts off my old beater Honda Accord to know better.

Oh, as a sidenote: on many maps, there is mention of a Beaver Creek Campground. I asked the South Fork Ranger district about this location and as I suspected, it’s an old, dispersed camping spot, not a formal campground. There are lots of decent camping spots along the six mile stretch from the cattle gate and it’s almost guaranteed you’ll be able to find a good one—just make sure to pay attention to specific closure markers in certain spots.

Fremont at our camp at 12,040′. The summit of Mount Silverheels is the highest point on the high background mountain. It’s 2.3 miles one-way to the top.

At 11,800’ a wide-open vista offers spectacular views of the Tenmile Range to the west and presents a good place to car camp. Note that I literally mean “car camp”. The winds are mighty strong across this ridge. In retrospect, we should have pulled off a short ways down the spur road (441) to the left of 659 and set up camp in a tree-protected area. We continued on a bit farther to another flat, open area that was at the foot of an unnamed 12,420’ hill and set up camp here. We set up our not-all-that-weather worthy car camping tent here (6-person, lots of room for two people and two pups). Despite moving our truck to divert some of the gusts, it was a lousy night of sleep as the tent walls snapped and pulsed in the non-rhythmic wind. Thus, actual car camping in your vehicle might be a good idea. Also, trying to sleep at 12,000’ when coming from 5,400’ in Boulder can be difficult, so a lower campsite may be a wise choice.

The road beyond this only goes about 0.4 miles to a closure point and in my opinion, isn’t really worth driving. Parking at the flat section roughly 6 miles from the cattle gate was perfect—the walk down to the end of the road only took about 10 minutes on nearly flat roads. The shelf road had suspect durability on the downhill side and my suspicions were confirmed where we saw a hapless Jeep stranded in a perilous rut where a small drainage crossed the road. If you do choose to drive, there are only a few small pull-offs and a tight, but usable, turnaround at the road closure.

Yolks! This poor Jeep was in a precarious position!

Enough, Man! What About the Hike!?

Right.

So starting from our camp, we walked 0.4 miles to the road closure, where an easy step-over stream crossing led us to wide-open slopes. A site labeled on most maps as “Iron Mine” is at the end of the road beyond the closure and could be accessed to pass the creek if needed. After that, it was hill-walking at its best. There are no trails, but we followed the path of least resistance, taking the northwest slopes to eventually connect to the west ridge. It’s steep, with about 2,000 vertical feet of elevation gain, but the footing is on solid, grassy terrain. This is a preferable option than the West Ridge Direct route, since that path involves cruising through willows and rockier, less-stable footing.

The lower part of the slopes on Mount Silverheels.

Fremont shows off on the northwest slopes that connect to the west ridge.

Aha! I found a cheerful Bumble hidden in the grass!

After gaining the broad west ridge at 13,300’, we had a pleasant ridge walk over to the summit. It was 2.3 miles from our camp to the flat summit, where a wind shelter was a welcome sight. A pair of 13ers, Boreas Mountain and Bald Mountain, loom to the east. 13,352’ Hoosier Ridge (the summit name of the highpoint of the ridge) and Red Peak C were to the north, and the full majesty of the Tenmile Range and distant Sawatch Peaks dominated the west, including the curving ramp of 14,265’ Quandary Peak. West looked down on a flat, peaceful valley and the tiny town of Jefferson.

Sheila approaches the summit.

Forget the views, we want a treat, woman!

The summit wind shelter on Mount Silverheels.

Hanging with Mystic on the summit!

The flowery summit ridge of Mount Silverheels.

The views to the south of South Park aren’t too shabby either. Good boy, Fremont!

We returned the way we came, though it wouldn’t be out of the question to muscle over to Hoosier Ridge for a bigger day. As it was, the 4.6-mile out and back was a great outing for our dogs and made for a great half-day hike (3.5 – 4 hours at a modest pace).

Truth be told, we were both weary from the non-stop wind the night before so a shorter day was perfect. We saw a pair of hikers on the summit who took the “standard” Hoosier Pass route, which works just as well. It’s an 8-mile out and back and the parking is much easier to access (off the top of the paved Hoosier Pass). That said, I found the remote feeling of FS 659 to be a unique Colorado environment, almost like something out of an apocalyptic movie. There was little human presence, but the decent road and airy metal towers created an atmosphere of a futuristic ghost town. If ever there was a hike that wagered its reputation on ambiance, this is it.

Cooling the paws on the 4th of July!

Who knows, maybe the spirit of Silverheels herself floats in the air in this scenic and inviting Centennial Peak.

One last drink before the ride home.

Driving Directions

Note: Google Maps is really screwy about the road numbers here (as of July 2017). It shows FS 655 when the road is actually marked as FS 659. I preferred to use CalTopo maps from GPSVisualizer.com to figure out the way to go. Google Maps seems to mislabel forest road numbers. Rest assured, this is an easy route to find once you’re actually there.

Take either Hwy 285 or CO 9 to the quirky town of Fairplay. Off CO 9, turn onto 4th Street. Turn left onto Beaver Lane (which has signs saying “National Forest Access”) and follow this level but heavily washboarded road about 2.9 miles to a right turn (where is another forest access sign here). Note that somewhere along the way, Beaver Lane turns into Beaver Creek Road—it’s the same road.

After turning right, continue a few hundred feet to the winter trailhead and a cattle gate. This is FS 659. Open the gate, pass through, and please close the gate before continuing here. The 4×4 road gets nicer here (oddly) and continues for 6.5 miles to the road closure. There is good camping all the way up to mile 6.0, but I’d suggest the sheltered spots off the left of FS 441 (marked). They are only a few hundred feet down the road. The only tough part of the road is the aforementioned hill, a bouncy but non-technical steep climb that I barely pushed up in normal 4×4.

Park in the open meadows at 6 miles in (near the power towers). Just after this, the road becomes a true shelf road with sketchy turnarounds. That being said it’s the same mellow grade and sparsely rocky surface as the rest of the road.

The post Mount Silverheels 13,822′ – Trip Report appeared first on Mountain Air.

Powered by WPeMatico

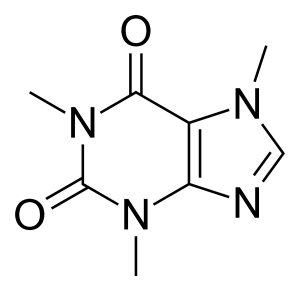

The weird thing about caffeine is that it is not a universal bad guy. In moderation, it has benefits that include increased energy, increased focus, and a low-level sensation of pleasure. Caffeine works by

The weird thing about caffeine is that it is not a universal bad guy. In moderation, it has benefits that include increased energy, increased focus, and a low-level sensation of pleasure. Caffeine works by